The authors of this article, a summary of an exhaustive document published on the CIRCERB website, are Clément Blanquet du Chayla, Charles Breton, Baptiste Giorgio, Mathieu Létourneau-Gagnon and Axel Lorenzetti.

This article was originally published in Voirvert magazine. You can read it here

Read the long version of the article "Post-COVID building, a necessary reflection"and the references provided by the authors.

A group of students at Université Laval's Industrial Research Chair in Eco-responsible Wood Construction (CIRCERB) have published their thoughts on post-COVID-19 building.

"Nothing will ever be the same again". This headline has been repeated frequently in the media since the start of the pandemic. The current health crisis is changing many aspects of our lives, not least our relationship with the built environment. Yet the importance of where we live is still very much missing from the public debate. What will the post-CIVID-19 era hold for the residential building sector?

A number of organisations, such as BOMA and ASHRAE, have published guides to good practice for limiting the risks of transmission in buildings. However, this approach overshadows a number of other systemic aspects that need to be considered if we are to rethink post-COVID buildings: buildings as a major industrial sector, as part of the city and as places to live. Whether it's because of its shared surfaces, its systems and equipment, or simply because of its traffic, buildings are often presented as a potential source of contamination. Using the example of a visit to an unclean public bathroom, Oppel questions the way we think about buildings and the risks posed by everyday objects: "Door handles, light switches, toilet handles, tap knobs are all ubiquitous, but are they necessary?

Construction as an industrial sector

Supply chains and prefabrication

The health crisis has affected all sectors of activity, disrupting value chains by complicating the transport of goods and stock management. In the construction sector, supply chains vary in complexity and origin. While some materials are sourced locally, others, such as steel and plastic components, are mainly sourced from international markets. In times of crisis, this dependence weakens the construction sector as a whole. Yet Canada has the resources, the businesses, the infrastructure and the know-how to build a resilient construction sector. Encouraging local processing of Canadian natural resources into high value-added products would help to shorten supply chains, ensure continuity and lead times in times of crisis, and limit the impact of fluctuations in international markets. This would stimulate the local economy and regional development, while helping to reduce the social and environmental impact of the construction sector's entire life cycle.

The prefabrication industry is moving the place of construction from the building site to the factory, an enclosed and controlled area, which offers a number of advantages that can facilitate the management of health risks. Working in a controlled environment makes it possible, among other things, to improve the efficiency of on-site construction; to offer greater flexibility in production hours; and to introduce more ergonomic workstations. The centralisation of activities, standardisation and mass customisation also make it easier to plan requirements and anticipate market fluctuations.

Making the most of the forestry and wood products sectors while encouraging prefabrication would support local businesses and the local economy, reducing - at least in part - our dependence on international markets. Wood is a lightweight material that is easy to process and offers good mechanical strength, making it particularly competitive for the low and medium-rise markets in North America. These qualities contribute to its compatibility with prefabrication. Wood is also a bio-sourced and renewable material. When managed sustainably, it can also contribute to efforts to mitigate climate change. Canadian forestry is among the most certified in the world.

Buildings as part of the city

Urban sprawl or densification?

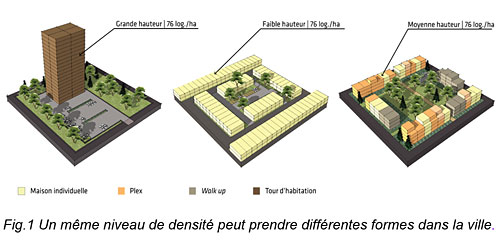

The confinement episode also revealed certain inequalities in the accessibility of outdoor areas and green spaces, in the proximity of services and in exposure to health risks in shared spaces. Communal areas carry a certain risk of contamination, which limits the individual's control over his or her environment. On the other hand, the single-family home continues to represent a certain social ideal; this secure and controllable alternative has motivated some people to leave their flat and the city. However, this demand leads to urban sprawl, which in turn leads to encroachment on farmland and natural areas, an increase in infrastructure and greater dependence on the car. It therefore seems difficult to reconcile the desired ideal with densification. While 75% of new buildings constructed in 2018 were multi-storey, the new mistrust of dense environments calls into question their long-term desirability.

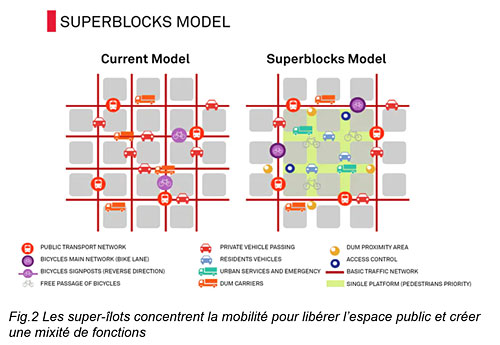

Proposing moderate density, quality public space and a mix of functions (housing, offices, shops) would make it possible to promote a good balance between densification and social acceptability by creating attractive housing, thereby avoiding increasing urban sprawl. In Quebec City, the Montcalm and Vieux-Limoilou districts are good examples. These neighbourhoods are dense enough to support local services and an efficient public transport system. However, because of their human scale, they limit the feeling of overcrowding, encourage community life and allow a sense of ownership to develop. In Barcelona, super-isles are restructuring urban mobility. These 400-500 m square units concentrate transport on shared roads and reduce car traffic within super-islands, creating new public living spaces to support the city's different functions. Initiatives of this kind help to create healthy and socially acceptable environments in the city, and thus make the concept of densification compatible with the issues of perception raised during the crisis.

The building as a place to live

New user needs

Buildings have a major impact on the well-being and physical and mental health of their occupants. The average Canadian spends almost 88% of his or her time inside a building, 6% in transport and 6% outside. However, physical distancing measures have transferred the time usually spent at work or outside to the home, which has become the main place to live. The health crisis, for example, has forced several companies to impose teleworking on their employees. This new reality of sharing accommodation between the professional and private spheres has led to a change in needs and exacerbated certain problems of comfort and well-being.

Changes in the use of the home introduce new needs and constraints, prompting a reconsideration of the usual comfort criteria. For example, the lighting and furniture traditionally sought for the home are less suitable for setting up an ergonomic teleworking workstation. However, the feeling of comfort varies according to the psychological and physiological needs of each individual, and largely depends on perceptions associated with the environment. Buildings are generally designed with financial (e.g. profitability) and normative (e.g. energy) objectives in mind. Comfort issues are still not given much consideration and are therefore not regulated to any great extent.

The changing context of post-COVID building should put comfort back at the heart of its priorities. To achieve this objective, the first solution is to adapt the layout of existing homes. The second would be to revise design practices to improve the quality and comfort of housing (e.g. extra rooms, soundproofing). However, these changes would entail additional costs that would necessarily be reflected in the price of the homes. To avoid limiting access to comfort, another possible solution would be to offer communal spaces to meet the new uses of housing. For example, the new housing standard should perhaps include shared teleworking areas, in the same way that they sometimes include a sports hall, swimming pool, laundry room, etc.

Wood as a means of improving comfort

Biophilia, or the love of living things, is an interesting solution for improving the perceived comfort and environmental quality of housing. In architecture, this term refers to a design that approximates the conditions of a natural environment, for example by maximising the presence of natural light, integrating plants or natural materials into spaces. Biophilia can help reduce illness and improve concentration and work performance by reducing and preventing stress and fatigue. These psychological and physiological responses tend to be universal, regardless of culture or geographical location.

Among the various ways of integrating biophilia into buildings, wood is a unique solution because of its naturalness and versatility (structure, cladding, fittings). Integrating wood would improve the environmental conditions of buildings. Its use enhances users' perception of the environment, comfort and well-being; seeing and touching wood induces an emotional and physiological response that has a positive impact on health. Wood also helps to reduce heart rate and stress levels. Consequently, the use of visible structural products or appearance products made of wood is an easy-to-deploy solution for improving the quality of life of users in buildings.

The health crisis: a lever to be exploited

Throughout history, health crises have often been catalysts for change. This should be the case for the current health crisis, to strengthen a local building sector, and to resolve the challenges of healthy densification where the comfort of occupants is at the heart of its concerns, alongside environmental and economic aspects.

But how can this post-COVID building model be made viable, without increasing socio-economic inequalities? A comprehensive approach must not limit the building to a simple site of contamination, but must also consider it as an industrial sector, a component of the city and a place where most people live. The current logic of economic optimisation is therefore hardly compatible with the establishment of post-COVID buildings. Its development will therefore require awareness and a willingness to adapt on the part of all players in society.

In Quebec, this awareness should include a major resource and sector of activity: forests and wood products. With its short, local value chains, its compatibility with prefabrication and the circular economy, its biosourced and renewable resource, its competitiveness in the low and medium-rise markets, its biophilic character and its effects on comfort and health, wood construction is a possible solution to the many challenges of post-COVID building.

Read the full article "Post-COVID building, a necessary reflection" and the references given by the authors.

Post-COVID building: a necessary reflection process